“How could we lose this forest?” It’s a history mystery we’d been working on for more than two weeks when Molly Tartt, a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution in western North Carolina, asked me that in an email. Indeed, how does a 50-acre forest vanish from maps and memory? No one knows where the forest is today, and few have heard of it. It’s more legend than fact at this point, it seems. Molly had been searching for some time and turned to FHS for help, fittingly, just before Independence Day.

A December 1939 newspaper article trumpeted the DAR’s plans for planting a forest to “memorialize the North Carolina patriots who took part in the struggle for independence.” An area that had been heavily logged and burned over would be reforested. The plan called for 60,000 trees to be planted on 25 to 40 acres set aside for the memorial (we believe it to actually be about 50 acres) in an area between Devil’s Courthouse and Mount Hardy Gap. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) announced at around the same time that they intended to plant 125,000 red spruce and balsam trees nearby to commemorate each North Carolina man who served in the Confederate Army. Today there is a wooden sign for that forest at the Mount Hardy overlook.

The DAR memorial forest project was part of a national conservation campaign by the organization leading up to its golden jubilee in 1941. The nation was facing the twin crises of economic depression and ecological disaster. It may have been the Dust Bowl years on the Great Plains, but in the Appalachian Mountains, forests and watersheds were suffering too. Though the land was within the Pisgah National Forest, logging companies had contracts to cut and proceeded to do so via railroad logging. The rail lines extended deep into the mountains, with the labor of men and machines combining to take a toll on the Southern Appalachian forests.

Map showing logging railroads in the early 20th century. The forest is between Devil’s Courthouse and Little Sam Knob. From Thomas Fetters, Logging Railroads of the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains: Volume 1, Cold Mountain, Black Mountain and White Top, pg. 227 (2007)

Railroad logging, as seen in the top photo, left behind landscapes like in the bottom photo. The slash and debris left by loggers was prone to fire, which happened on the land where DAR dedicated its forest. Both photos were taken somewhere in Haywood County, NC, about 20 years before the DAR plantings. The memorial forest is located in southern Haywood County. (FHS4310 and K_1-166337)

To combat the twin problems of human and environmental poverty, President Franklin Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933. Women’s groups of all stripes wanted to do their part, and in the DAR’s case, the jubilee provided motivation. According to the organization’s “DAR Forests” webpage:

In 1939, the President General, Mrs. Henry M. Robert, chose the Penny Pine program as one of her Golden Jubilee National Projects. Each state was to have a memorial forest, beginning in 1939 and culminating in 1941 on the NSDAR 50th Anniversary. Each chapter across the country was to pledge, at the very least, one acre of pine seedlings. Five dollars an acre at a penny each equaled 500 trees. The Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC), under the supervision of the U.S. Forestry [sic] Service, would do the actual work of planting and care.

The DAR’s interest in Appalachia’s forests has deep roots, stretching back to the Progressive Era and the debates over the need to protect the headwaters of navigable waterways in the East. According to environmental historian Carolyn Merchant, “In 1909 Mrs. Mathew T. Scott was elected President General of the 77,000 member Daughters of the American Revolution…. Mrs. Scott was an enthusiastic conservationist who encouraged the maintenance of a conservation committee consisting of 100 members representing every state.” (One of the women deeply involved in the conservation committee was Gifford Pinchot‘s mother, Mary.) Under Scott’s leadership, DAR conservation efforts included working towards the “preservation of the Appalachian watersheds, the Palisades, and Niagara Falls.”[1]

By then, forest conservation leaders in North Carolina had been agitating for nearly two decades for state and federal protection of forests and watersheds. They formed the state’s forestry association in 1911, and its forest service in 1915. And although the Weeks Act of 1911 had led to the creation of the Pisgah National Forest in 1916, where the proposed memorial forest would be located, federal management didn’t immediately translate into better environmental conditions. Logging companies carried out their existing contracts and logged what they could—in this case taking “one of the best virgin stands of spruce in the United States,” according to a 1941 newspaper report, and leaving “only a few scattered trees of merchantable species due to clearcutting” and fire—before turning over land to the Forest Service.[2]

In the late 1930s the conservation (and patriotic) ethos of the local and state DAR chapters was strong and members were highly motivated to take action on many fronts. This can be seen through reports about the state chapter in the annual national congress proceedings, beginning the same year President General Robert announced the golden jubilee project.

Proceedings of the Forty-Eighth Continental Congress of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Washington, DC, April 17-21, 1939: “North Carolina—Mrs. Hugh McAllister, Chairman [of conservation]. Chairman urged legislation for eradication of Dutch elm disease and the planting of a memorial forest in Pisgah National Forest in 1940. Thirty acres have already been reforested and 20 acres trimmed. A total of 37,444 trees planted.”(114)

Proceedings of the Forty-Ninth Continental Congress, April 15-19, 1940: “North Carolina—Mrs. Hugh McAllister, reports that Golden Jubilee Forest has been completed and will be dedicated on May 15th. Conservation of holly and other evergreen trees has been urged and 54,331 trees planted.”(120)

Proceedings of the Fiftieth Continental Congress, April 14-19, 1941: “North Carolina—Mrs. Leet A. O’Brien, Chairman. Golden Jubilee Memorial Forest of 50 acres planted and dedicated May 15, 1940; 3,184 other trees were used in beautification projects.”(156)

On May 15, 1940, six months after announcing the planting project, state and national DAR leaders drove out a winding mountain road from Waynesville to the Pisgah National Forest for the dedication ceremony along the Blue Ridge Parkway, then under construction. Mrs. Robert traveled from her home in Maryland to accept the forest on behalf of the national organization, and Mrs. McAllister presided over the proceedings. The only man invited to participate in the program was the U.S. Forest Service’s H. B. Bosworth, Pisgah National Forest’s supervisor, who briefly explained the federal government’s reforestation projects on that windy day. You can see the ladies trying to keep their hats on in the few remaining photos.

Pisgah Forest Supervisor H.B. Bosworth addresses the gathering. The women aren’t saluting; they’re holding on to their hats.

The site was to be marked with a bronze tablet mounted on a large boulder, like in the second photograph down below, and placed at a parking area adjacent to the forest. We don’t know where the above photo is taken, or what road that is above them (or if it’s even a road). A photo from the ceremony (below) shows a sign attached to two poles. We don’t know if the sign is bronze or wood, or if a tablet attached to a rock was ever installed. (Demand for bronze after U.S. entry into World War II meant postponing the casting of the UDC tablet, whose ceremony was two years later, until after the war.) The reforestation effort didn’t begin until 1941, when the seedlings were mature enough to plant.

This is the only photo we have seen showing the sign. We’ve recently learned the poles were made of brass.

Illinois Society Daughters of the American Revolution at dedication of D.A.R. Diamond Jubilee cooperative forest plantation on the Shawnee National Forest, Illinois, 1940. Presumably the one in North Carolina would have used a rock of similar size. At far left is Margaret March-Mount, who launched the Penny Pines campaign. (FHS Photo Collection, R9_419109; USFS photo 419109)

It’s not known when the forest went “missing.” I’ve found only a single mention of the DAR forest after 1942; it was in a 1951 newspaper column “Looking Back Over the Years” that recapped news from ten years before, and it was about planting the seedlings. The UDC forest planted was “misplaced” for a few decades but was relocated and rededicated in 2002.

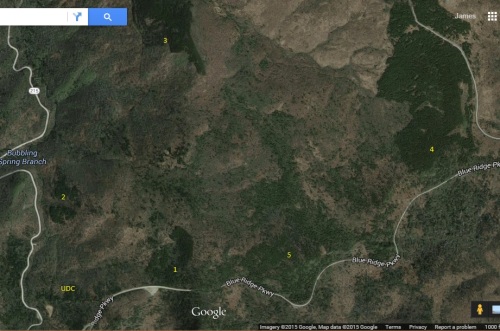

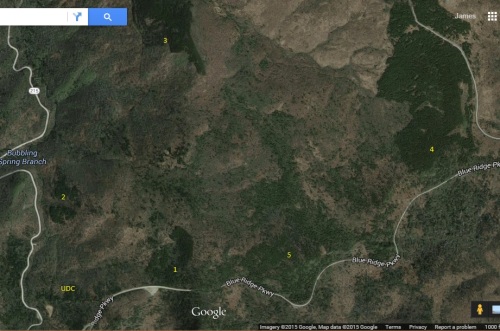

Research conducted here at FHS and in western North Carolina has narrowed the DAR forest to being around the Devil’s Courthouse overlook at mile marker 422, on the north side (see map). It’s rather ironic that alongside the newspaper article in the April 24, 1941, announcing the arrival of the spruce seedlings for planting is one about the romantic comedy film opening in town that weekend. The now-forgotten film The Man Who Lost Himself centers around a case of mistaken identity and redemption that of course ends happily. If you know anything about this forest that was lost and possibly mistaken for another, please email me at James.Lewis AT foresthistory.org. We’d like to identify this forest and write a happy ending for this story, too.

“X” marks the possible location of the DAR forest. Click on the map to enlarge.

UPDATE: 7/29/2015

Since the original post went up, we received the map below courtesy of Molly Tartt. She received the copy from a former Forest Service employee. The map is dated three days before the newspaper article mentioned above that the seedlings had arrived.

US Forest Service map of the area showing the two memorial plantations, dated April 21, 1941. Click the map to see it enlarged. The chain-like symbol with the line through the links represents the county line and the same symbol without the line is either a road or a trail.

Close-up of the area from the same map. The parkway runs on the south side of both forests.

This satellite photo indicates where the forest is located today (1). It’s curious that there are other clusters of what appear to be similar species in the vicinity, as indicated by numbers 2-5. It’s not known if these were planted or naturally regenerated.

UPDATE: 10/18/2016

A re-dedication ceremony was held on October 14, 2016, during which a new sign commemorating the original dedication and explaining the impact of logging on the area was unveiled. The ceremony attracted about 200 people, including the national leadership of the DAR, and was covered by local newspapers the Transylvania Times and the Smoky Mountain News.

The new sign, with the DAR forest in the background.

Blue Ridge Parkway Superintendent Mark Woods addresses the crowd during the ceremony. Lorie Stroup, acting district ranger for the Pisgah National Forest, spoke on behalf of the U.S. Forest Service.

The DAR Jubilee Forest, as seen from Devil’s Courthouse, Oct. 14, 2016.

Many thanks to Molly Tartt and to the researchers and historians at the DAR library in Washington, DC, for their help and to all who provided photos and other sources.

NOTES

[1] Carolyn Merchant, “Women of the Progressive Conservation Movement: 1900-1916,” Environmental Review Vol. 8, No. 1: 68-69.

[2] “Patriotic Groups Planting Memorial Forests in Pisgah,” Waynesville Mountaineer, April 24, 1941.

Read Full Post »