Austin Cary, one of the great unsung heroes of American forestry, was born this date in 1865 in East Machias, Maine. A Yankee through and through, he found professional success in the South, eventually becoming known as the “Father of Southern Forestry.” In 1961, twenty-five years after Cary’s passing, his biographer Roy R. White wrote of him:

In contrast with his more renowned contemporaries, Austin Cary was an obscure logging engineer in the Forest Service. Yet the story of the life and work of this latter-day Johnny Appleseed has reached legendary proportions in the southern pine country. Cary, a New England Yankee, dedicated himself to the awesome task of bringing forestry and conservation to a region reluctant to accept, and ill-equipped to practice, these innovations. His success places him in the forefront of noted American foresters and his character warrants a position peculiarly his own.

What makes Cary an intriguing historical figure was his unorthodox, nonconformist approach to life and work. He hailed from an old, well-to-do family whose wealth made him financially independent. By the time he graduated at the head of his class from Bowdoin College, where he majored in science with emphasis on botany and entomology and received the A.B. degree in 1887 and the M.S. in 1890, he was already known as a “lone wolf” comfortable tramping alone in the woods. Despite his refined upbringing, he was called blunt and tactless, and that was by his friends. The “dour New Englander” struggled in several different jobs before finding his niche, in part because of his personality. He moved from industry forester in New England to college instructor (Yale Forest School, 1904-1905; Harvard, 1905-1909), and then in 1910, to logging engineer in the U.S. Forest Service.

Between 1898 and 1910, Cary kept asking for a job with the Forest Service. Chief Gifford Pinchot refused to hire him, though, perhaps because of his personality, more likely because of philosophical differences. Cary strongly believed that private forestry, and providing economic incentive to private land owners to hold land and reforest it, was the nation’s best hope for conserving America’s forests, whereas Pinchot had staked his agency’s position on the federal government dominating land management. Only after Pinchot’s dismissal in 1910 did Cary get hired by the Forest Service—by Pinchot’s replacement and Cary’s former boss at Yale, Henry Graves, who supported Cary’s position to some extent.

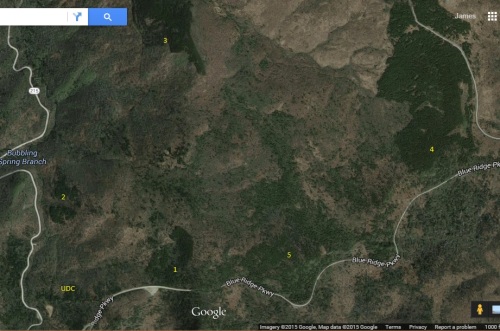

Carl Schenck wrote of Austin Cary, here photographed in Florida in 1932, “[He] was as good with the axe as if he were a Canadian lumberjack.” (FHS Photo Collection)

Cary didn’t fit in there and relations deteriorated. Given the choice of assignments in 1917, Cary choose the South, where the Forest Service had little presence and he could create his own program. “Significantly,” White tells us, “he planned an appeal to southern landowners and operators, large and small. It would be necessary, he knew, to influence a people generally hostile to strangers, notoriously averse to change, and shackled by a near-feudal economy.” The “lone wolf” found a home in the southern woods, which were (and still are) largely privately owned and at the time in need of intervention. Though his title was that of logging engineer, he operated as a roving extension forester.

When he arrived, the South’s First Forest was nearly exhausted. “Into the void of southern forestry he intended to introduce forest practices which would assure a second timber growth on the barren, smoldering land,” wrote White, where fire was widely used. The Forest Service campaigned to eliminate it from southern forests; Cary defied them because he saw the ecological role fire played, and instead encouraged landowners to experiment with what are now called prescribed burns. Somehow this direct, straight-shooting Yankee won over Southern landowners. He was not allied with one large company and they didn’t really think of him as Forest Service; they were charmed by “his disrespect for propriety and authority” and his personality. Their conservatism matched his, and he became a staunch defender of their practices and land rights. This culminated in a bitter denunciation of the New Deal–era federal land acquisition in 1935, captured in an open letter to President Franklin Roosevelt that Forest Service officials initially tried to suppress. In the end, they decided it was less painful to suffer his opposition than to silence him, and allowed the letter to be published in the Journal of Forestry. Thumbing his nose at the ultimate authority was his last significant action before he retired in 1935.

“With a new forest turning the South green once again,” he decided to “‘bang around less…live more quietly'” and retired to Maine. He died on April 28, 1936. The well-managed private forestlands in both New England and the South are just a portion of his impressive legacy.

◊◊◊◊◊

You can read more about Austin Cary and his legacy in Roy White’s article “Austin Cary: The Father of Southern Forestry,” where all quotes in this article are from, and by exploring the many resources we have on him listed below:

The Austin Cary Photograph Collection contains images taken by Cary between 1918 and 1924 during his early years of working in the South for the Forest Service. The photographs document forestry and turpentining practices in the pine forests of the southeastern United States. We have a finding aid and online photo gallery.

Interviews with several foresters who discuss the positive influence of Cary reside in the “Development of Forestry in the Southern United States Oral History Interview

A 1959 oral history interview with Charles A. Cary includes discussion of his family background and his uncle Austin Cary.

Some of Cary’s acidic nature is evident in his correspondence with Carl A. Schenck in this Journal of Forest History article.

We also have two folders’ worth of materials in our U.S. Forest Service History Collection.

His papers are housed at the University of Florida.