On May 26, 2016, Jack Ward Thomas lost his battle with cancer. Thomas started his U.S. Forest Service career as research wildlife biologist in 1966 and ended it in 1996 after serving for three years as Chief. Historian Char Miller offers this remembrance.

Jack Ward Thomas, the 13th Chief of the U.S. Forest Service, didn’t suffer fools gladly. That he managed to overlook my foolishness at Newark Airport is something of a minor miracle.

We were to have rendezvoused at that crazy-busy airport so that I could drive him to a symposium held at Grey Towers NHS, Gifford Pinchot’s former home in Milford, PA. This was shortly after President Bill Clinton had tapped Jack in 1993 to be the chief, and because the new chief had no interest in having law enforcement ferry him from place to place, someone on Jack’s staff had the bright idea that I’d make a fit chauffeur.

The driving part was simple; the connecting, not so much. We arrived at different terminals, at different times, and my ill-fated strategy was to pick up the rental car first and then meet Jack at the departures level. How I thought this was going to happen—I didn’t carry a cellphone, and knew enough to know that you couldn’t park in front of the terminal—is beyond me. As it was, it took me more than hour to break through the circling chaos of cars, taxis, and buses and locate a New Jersey State Police officer willing to let me illegally double park, despite his doubts: he had never heard of the Forest Service, let alone its chief, a consequence, perhaps, of the Garden State not having a national forest. In any event, I raced inside, found Jack, apologized profusely, and endured—well, let’s call it a sharp-edged, if bemused, stare.

Then we started to talk, a conversation that lasted for more than twenty years and only ended on May 26, with Jack’s death at age 81.

During that initial car ride, I mostly asked lots of questions; after our awkward introduction, how much more foolish did I wish to appear? Thankfully, Jack liked to talk, and he was by turns funny, insightful, and blunt. What I was most interested in was how and why he had been selected as chief. The president’s choice had been controversial inside the agency and beyond the Beltway, and I was curious about the transition. Not that I put it so directly, instead tiptoeing up to the issue: Jack was having none of that, asked me what I wanted to know, and over the next hour laid out who said what to whom and why. Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, he had been keeping a detailed diary, an astonishing record that several years later he asked me to evaluate for its potential for publication. There, in rough form, was the basis for his incisive discussion that afternoon of the policy goals and political maneuverings that led to his becoming chief.

Once published, The Journals of a Forest Service Chief (2004) became the indispensable, insider’s guide to environmental politics in the Clinton Administration. Even more significantly, and why I continue to assign it in my U.S. public lands class, the book exposes the enduring tensions between the White House, Congress, and the Supreme Court, much as Harold Ickes’ Secret Diaries (1953) did for the Roosevelt and Truman years. My students are as stunned by Jack’s revelations about DC power dynamics as they are moved by his emotional responses to such traumas as the deadly 1994 South Canyon fire in which 14 firefighters lost their lives. One moment stands out: while Jack talked to the grieving fire crew boss, and assured him that he “was not alone in this thing,” the firefighter “put his face in my chest, and when my arms encircled him, he began to sob uncontrollably, and so did I.” Jack wore his heart on his sleeve.

He was loyal to the core, too, as I discovered in 1995 after publishing a column urging the directors of federal land-management agencies to “come out swinging” in response to mounting right-wing attacks on them, some verbal, some violent. Within days, I received a lengthy, handwritten rebuttal from Jack: he understood my frustration but took umbrage at my suggestion that he and his colleagues were silent, that they did not have their employees’ backs. In taut prose, he outlined how wrong I was. Point taken.

His other writing was just as tight, just as pointed. That comes through loud and clear as you leaf through the three-volume set of his prose that the Boone & Crockett Club published in 2015: one contains Jack’s memoir-like reflections on his life and activism, another his experiences riding in the “high lonesome,” and the third is filled with hunting yarns from around the world. In print, he comes across as he did in the flesh: keen and curious, well and deeply read, self-assured. Jack did not tie himself, or his sentences, in knots.

Like this declarative insight, which he borrowed from botanist Frank Egler: “Ecosystems are not only more complex than we know, they are more complex than we can know.” That our knowledge will always be partial, incomplete, did not mean, as Jack stressed in speech after speech, that it was a mistake to expand our understanding of nature’s infinite variations. As a wildlife biologist he had spent a lifetime studying the impenetrable, and had loved every minute of it. Neither did he think that we should hesitate to revise our policies as new data emerged about the environment’s complexity; his tenure as chief was spent in good measure pressing the concept of ecosystem management into the Forest Service’s stewardship practices.

What Jack insisted on was that we not kid ourselves about our capacities. “Of all people,” he once argued, “scientists should be acutely aware that we know so little and that there is no final truth.” To believe otherwise was just plain foolish.

President Bill Clinton shakes hands with Chief Thomas during a photo op in August 1996 in Yellowstone National Park. In the background, from left to right, are Brian Burke, Deputy Undersecretary of Agriculture; Richard Bacon, Deputy Regional Forester of Region 1; and Dave Garber, forest supervisor of the Gallatin National Forest.

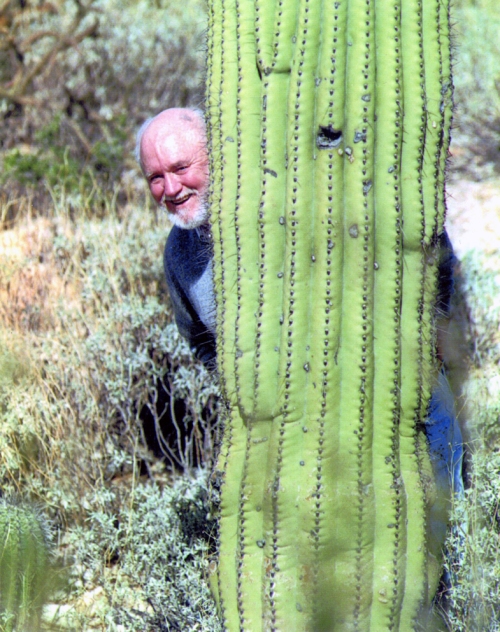

In this undated photo from his time as chief, Jack shows his playful side by hiding behind a sauguaro cactus.

Thomas with Jim Lyons, Undersecretary of Agriculture, in the Eagle Cap Wilderness on the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest in August 1996. On occasion Jack brought along political leaders and others on his backcountry trips to show them the importance of wilderness and “do a little politicking.”

***

Char Miller is the W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College and author of America’s Great National Forests, Wildernesses, and Grasslands. He wrote the foreword to Jack Ward Thomas’ Forks in the Trail (2015) and discussed his career in Seeking the Greatest Good: The Conservation Legacy of Gifford Pinchot (2013). You can learn more about Thomas on the Forest History Society’s U.S. Forest Service History website or by visiting Jack’s own website. You can read Chief Tom Tidwell’s reflections about Thomas’s impact on the Forest Service in this article by columnist Rick Landers of Spokane’s Spokesman-Review.