Everyone knows Smokey Bear, Woodsy Owl, and maybe even Ranger Rick Raccoon, but there are many other forest and forestry-related fictional characters that long ago fell by the wayside. Peeling Back the Bark‘s series on “Forgotten Characters from Forest History” continues with Part 9, in which we examine Sam Sprucetree.

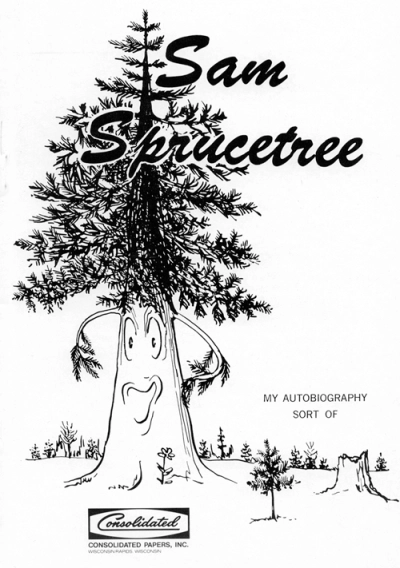

Sam was a character created by Consolidated Papers, Inc., of Wisconsin to help tell the role of forest management in paper production. Sam’s autobiography—an 8-page booklet titled “Sam Sprucetree: My Autobiography Sort Of”—appeared sometime in the 1970s, probably in 1978. For reasons that will soon become clear, it was probably Sam’s only appearance.

In the tradition of Woody and Ev’rett, Sam is another in a long line of anthropomorphized trees created to help explain a complex topic to the general public, in this case a public that was hearing conflicting information about forest management practices. Based on a code printed on the back of the booklet and the remark in the “introduction” about Consolidated’s forestry program having started “more than four decades ago,” I think this was printed in 1978. At the time, both public and private foresters were experiencing a great deal of scrutiny and criticism about clearcutting as a result of the Bitterroot and Monongahela controversies. My guess is that Consolidated Papers produced Sam’s story—with its explanation of how its foresters instituted selection cutting on company land—partly to counter the blowback from the clearcutting controversies.

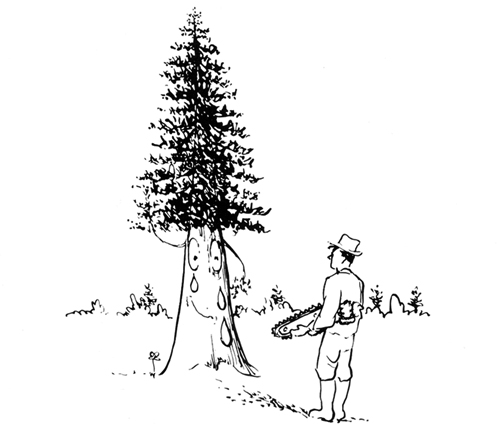

In a curious twist on the anthropomorphized tree genre, Consolidated Papers opted to let Sam tell his own story. A straight-forward history of the company and its longtime embrace of forest management couldn’t possibly match the appeal of a thinking, feeling tree, nor would a tale told in the third person. In “Sam Sprucetree: My Autobiography Sort Of,” when a forester comes by and marks his trunk with paint, Sam knows that the end of his life is at hand (or branch), which prompts him to share his story. It’s a classic take on a rich, full life: there’s the requisite childhood trauma and obstacles to overcome, but unlike many of today’s celebrity memoirs, Sam doesn’t complain or whine about the hand life dealt him. In fact, in the face of death, he’s at peace with his fate (though you’d never know it by looking at his facial expression on the cover).

Click on the image to read the book. Don’t wait for the movie. But if you do wait for the movie, rumor has it that either one of the apple trees from “The Wizard of Oz” or Daniel Day-Lewis will play Sam.

Sam has borne witness to the changes in attitudes towards trees and forests over the last 75 years or so. He has seen it all during his long life, a life that started in the “cut and get out” days of the early 20th century, when loggers indiscriminately logged white pine in the Lake States region. Sam shares the lessons he’s learned from each phase of his life—that early loggers were bad, fire is evil, foresters are heroic, and being designated for cutting and turned into pulp is an honor—perhaps the greatest honor for a spruce tree. His noble death enables him to realize a lifelong dream.

Sam sheds tears of joy when he finds out that he’s been “scheduled for a ride.”

Like many of these publications, this one does do a good job of explaining the topic for a general audience of all ages. What I find interesting after having read so many of these promotional publications, however, is not what’s in print, but what’s not in print. While there’s a very exciting recounting of how a team of oxen nearly dragged a log over Sam and killed him when he’s just a sapling, there’s no mention later of any threats from mechanized vehicles operating in the woods, nor from chainsaws or other modern methods of logging. Perhaps the PTSD (post tree-matic stress disorder) he suffered when threatened by the log or later by fire has rendered him mute on the subject. It might also explain his weird vision of what fire looks like.

Sam survives being nearly killed by oxen only to be threatened by fire (below). He didn’t need a tree surgeon for his injuries, he needed a tree psychologist.

The booklet ends with Sam knowing that he’ll be logged. Which begs the philosophical question: If an anthropomorphized tree falls in the forest, does he make a sound?