If you find yourself in New York’s Adirondack Park, be sure to add a walk through Fernow Forest to the Forest History Bucket List of things to do while there. It’s a nice place to spend an hour or so stretching your legs and learning about Bernhard Fernow, an important yet underappreciated figure in North American forest history, while looking at a sample of his work in New York.

If you find yourself in New York’s Adirondack Park, be sure to add a walk through Fernow Forest to the Forest History Bucket List of things to do while there. It’s a nice place to spend an hour or so stretching your legs and learning about Bernhard Fernow, an important yet underappreciated figure in North American forest history, while looking at a sample of his work in New York.

Make no mistake: visiting either forest in the United States named for Bernhard Fernow is worthwhile. In West Virginia is the Fernow Experimental Forest on the Monongahela National Forest, operated by the U.S. Forest Service. This 4,300-acre forest offers mountain biking trails and other recreational activities. I’ve not been there yet, but it’s on my bucket list. The one in the Adirondacks is under the control of the state’s department of natural resources.

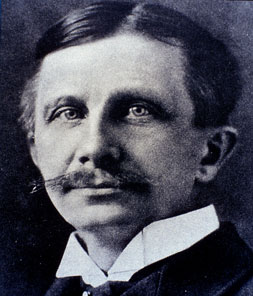

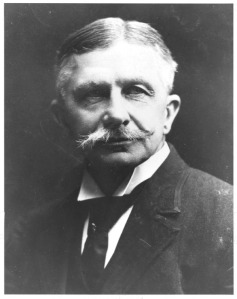

It’s fitting that Fernow has two forests named for him. As chief of the U.S. Division, predecessor to the U.S. Forest Service, of Forestry he placed the small bureau firmly on scientific footing, writing scores of reports and conducting and coordinating research. Such efforts during his twelve years with the division (1886–1898) make him one of the founding fathers of American forest research, something he rarely receives recognition for. He is better known as the father of professional forestry education in North America. A long-time advocate for forestry education in the America, in 1898, he left the Division of Forestry to establish the New York State College of Forestry at Cornell University. It was the first professional forestry school in the United States (meaning, the first school to offer a college degree). After the school shut down in 1903 (see below), he taught at Yale’s forestry school and elsewhere for a few years. In 1907, he founded the forestry program at Pennsylvania State College’s main campus, teaching there in the spring of 1907 before heading to the University of Toronto and establishing Canada’s first forestry school, where he stayed until his retirement in 1920. The Fernow Forest in West Virginia is a nod to his research leadership; the one in the Adirondacks is one to his work in forestry education.

Fernow located Cornell’s experimental forest on 30,000 acres in the heart of the Adirondack State Park, a decision that would contribute to the demise of the school just five years after it opened. He clearcut the hardwood forest and ordered the planting of the commercially valuable species of white pine and Norway spruce as part of his effort to demonstrate that good forest management could pay. The school sold the lumber to the Brooklyn Cooperage Company, which had set up a mill on the site. Unfortunately, the operation was near several wealthy landowners who didn’t care for the noise and smoke coming from the school’s woods and petitioned the governor to shut down the school. He complied by eliminating funding for the school in 1903, effectively killing it.

But walking the Fernow Forest Trail in the Adirondacks can help a visitor understand what he was trying to accomplish. It was no small goal he had in mind, trying to teach his students the fundamentals of forestry and demonstrate to an indifferent country that forest management could turn a profit and produce a steady supply of lumber.

Located on a 68-acre tract that was once part of the school forest, the trail is a under a mile long, a well-groomed dirt path that’s fairly level and easily navigated. Much like Fernow the historic figure, it’s easy to overlook the trail along the road. Marked by an underwhelming sign, with parking in a pullout on the shoulder of NY 3, you have to pay attention when looking for it or you’ll go right by it. Unlike the Carl Schenck Redwood Grove in California, which is a good distance from the road, you never quite get away from the sound of cars in Fernow Forest.

Also unlike Schenck Grove, which celebrates the man and his ebullient spirit, Fernow’s trail is like him—all business, with an emphasis on education. This trail not only informs you about Fernow and the school, but also how and why he was managing the land, what has occurred on the land since the school’s demise, and a bit about the geological history of the land. The forest is no longer actively managed except for trail maintenance done by students from nearby Paul Smith’s College (also worth visiting). With that background, let’s get going.

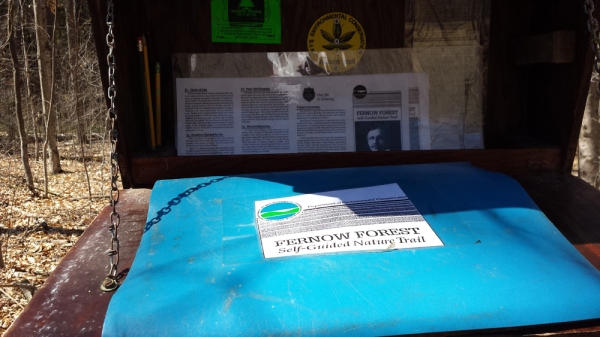

When you start the walk, be sure to sign in at the trailhead so the state knows how many people use it. Borrow a laminated trail map, which interprets the different stops along the trail.

Be sure to peruse the sign-in sheets to see where others visited from. Someone from France had visited not long before I did.

At stop #1, you learn that you’ve been walking through a northern hardwood forest and are about to transition to the softwoods of the Fernow Forest (which begins at stop #2). It consists largely of Norway spruce and eastern white pines (indicated with signs at stops 4 and 5, respectively) planted at Fernow’s direction in rows. Most rows are still visible, running perpendicular to the trail.

Stop #3 commemorates the man himself with a tablet attached to a massive boulder.

The tablet reads: “This Forest Plantation and Trail Dedicated to BERNHARD E. FERNOW 1851 – 1923.” It includes this quote from Fernow: “I have been unusually lucky to see the results of my work. I have been a plowman who hardly expected to see the crop greening, yet fate has been good to me in letting me catch at least a glimpse of the ripening harvest.”